"You have no idea, how much poetry there is in the calculation of a table of logarithms."

Introduction

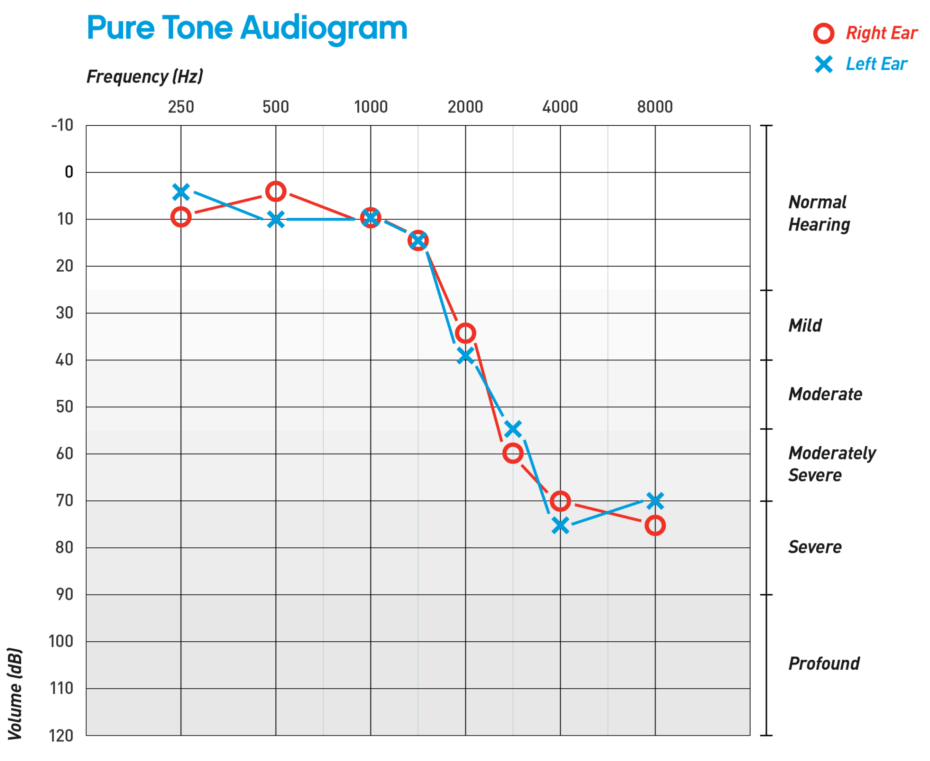

As far back as I can remember, my father always had hearing problems. Because of this, every once in a while, he had to undergo an "audiogram" (a hearing test). An audiogram is a chart that looks like the figure below.

On the horizontal axis, you can see frequencies ranging from 20 to 10,000 (even though humans are capable of hearing sounds up to 20,000 Hz). But the vertical axis represents hearing levels in a unit called decibels. A decibel literally means "ten bels", but the bel itself is a logarithmic unit. This means that 40 decibels is actually ten times stronger than 30 decibels! But why should that be? Why use a logarithmic unit to measure someone's hearing? Searching for an answer to this question leads to a deep understanding of logarithms, the brain, perception, and information.

Background

Gustav Theodor Fechner, a German physicist, philosopher, and psychologist, is the founder of what we now know as "psychophysics". Fechner studied the relationship between physical stimuli and the sensations (perceptions) that arise from them. His studies opened up a whole new avenue for understanding the human psyche and its relationship with the physical world. Fechner was the student of another German physicist and psychologist named Ernst Heinrich Weber. Weber noticed that "the minimum increase of stimulus which will produce a perceptible increase in sensation is proportional to the pre-existent stimulus".

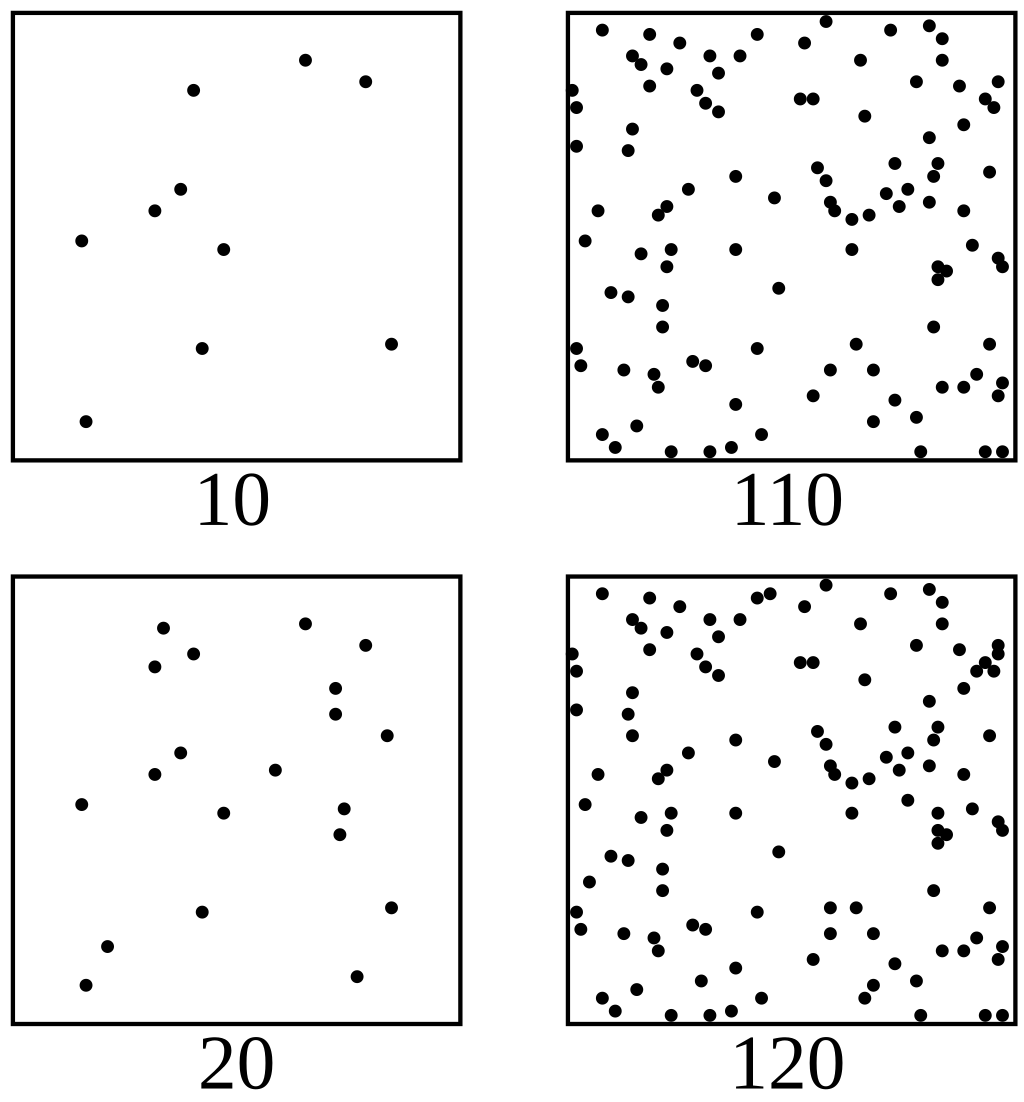

To understand this concept, look at the figure below: on each column there are 10 more dots in the below square than in the upper, however, our perception of the difference is clearly different—the increase in the number of dots on the left column is visible but not as much on the right column.

In 1860, Gustav Fechner published a seminal book titled Elemente der Psychophysik (Elements of Psychophysics), in which he explored foundational ideas about human sensation. He proposed that sensory change is best understood as a contrast across scales, that is, the detection of change relies on relative differences rather than absolute ones. Fechner observed that in order to notice a difference in a stimulus (such as brightness or weight), the change must be a constant proportion of the original stimulus. In other words, the brain is a detector of ratio-based change.

For example, if you are given a 1 kg weight and it is increased to 2 kg, you immediately notice the difference. However, if you're given a 10 kg weight followed by an 11 kg weight, the same 1 kg increase is barely perceptible. To detect a comparable change in the second scenario, the weight would need to double from 10 kg to 20 kg. This minimum proportion of change that is just barely perceptible is known as the just-noticeable difference (JND).

Fechner concludes:

The perceived change in stimuli is inversely proportional to the initial stimulus

In mathematical terms, if we denote a small change in perception as $dp$ and the stimulus as $S$, then the relationship can be written as:

$$dp = \alpha \frac{dS}{S}$$where $\alpha$ is the proportionality constant. This is called the Fechner law. If we start at some initial stimulus $S_0$ and then change it to $S$, the total change in perception would be:

$$p(S)-p(S_0)=\alpha \int_{S_0}^S \frac{dS'}{S'}=\ln \left(\frac{S}{S_0}\right)^\alpha$$or more simply:

$$p=\alpha \ln \frac{S}{S_0}$$This shows that the relationship between stimulus and perception is logarithmic. That is, when the stimulus is multiplied, the perception only increases additively. This principle is not limited to weight or auditory perception; it applies broadly across all sensory modalities.

For example, our visual system can detect luminance over a range of more than $10^9$ times, yet our perception of brightness increases linearly across this range. Similarly, our sense of taste operates on a logarithmic scale. The tongue is highly sensitive to small differences in weak stimuli but becomes less discriminating as intensity increases. Take sucralose, an artificial sweetener found in many diet sodas: although it is up to 600 times sweeter than sugar in terms of concentration, the perceived increase in sweetness is relatively modest, because perception scales with the logarithm of stimulus intensity.

Logarithmic scaling also extends beyond the traditional five senses. It applies to our perception of distance, time, and even decision-making. According to Hick's Law, the time it takes to choose among $N$ alternatives increases only logarithmically: $\text{reaction time} \propto \log(N)$. This raises a fundamental question: Why does our perception follow a logarithmic relationship with the stimuli we receive from the world?

The Log-Dynamic Brain

A wealth of psychological and neuroscientific research reveals a profound truth: our minds and bodies interpret the world not through absolute values, but through ratios. This ratio-based perception is so deeply embedded in our cognition that it shapes how we see, hear, taste, and even think. The Latin root logos, meaning reason, word, or ratio, is at the heart of this idea. It forms the basis of words like rationality (our capacity to make sense of the world through proportion and relation) and logarithm (literally, "the ratio-number").

This fundamental orientation toward ratios forms the backbone of contextuality, the hallmark of human cognition. We rarely judge things in isolation; instead, we compare them to surrounding elements. One well-documented study, for example, found that patrons in a bar were significantly more likely to order German beer if German music was playing in the background. Their decision was not based solely on their personal preference, but on a subtle contextual cue, a ratio between environment and choice.

This same principle explains why a \$10 sandwich may feel expensive at a food truck but cheap at an upscale airport lounge. Or why the same glass of wine tastes better if you're told it's a \$100 bottle rather than a $10 one. In all these cases, the value isn't perceived in isolation; it's inferred from its relative position in a broader sensory or social context.

At a neural level, this tendency is embodied in associative memory. The brain doesn't store facts like a computer; it stores relationships—patterns of co-occurrence. These internalized "ratios" between stimuli, actions, and outcomes enable us to navigate the world efficiently, filling in gaps and adapting flexibly to new situations. We don't just see the world as it is; we see it in proportion to everything else.

Recent studies of the brain offer valuable insights into why both the brain and the body often operate according to logarithmic principles. One of the earliest observations in neuroscience is that neural activity does not follow a normal (Gaussian) distribution. Instead, it follows a log-normal distribution: the majority of neurons fire at relatively low frequencies, while a small minority fire at much higher rates.

This small group of high-frequency "fast burster" neurons holds a special status. They not only remain consistently more active but also form more connections with other neurons. Acting as central hubs, these neurons help organize brain activity into a hierarchical network structure, supporting efficient communication and integration across different regions of the brain.

György Buzsáki and colleagues showed that synaptic weights, axonal bouton sizes, and cortical firing rates all follow heavy-tailed log-normal distributions, implying multiplicative growth processes operating across scales. This "log-dynamic" architecture means a small subset of very strong hubs dominates network throughput, while many weak links provide flexibility.

Such statistics naturally produce gain curves consistent with Weber–Fechner: a proportional increment in presynaptic drive yields an additive change in postsynaptic potential once signals are expressed in log units. Computational models confirm that skewed, log-normal weights maximize information flow under metabolic constraints.

The stimuli around us follow the power law in many cases, and our cognitive systems are adapted to a dynamic-range compression for optimal transfer of information.

Information Space: A Logarithmic Space

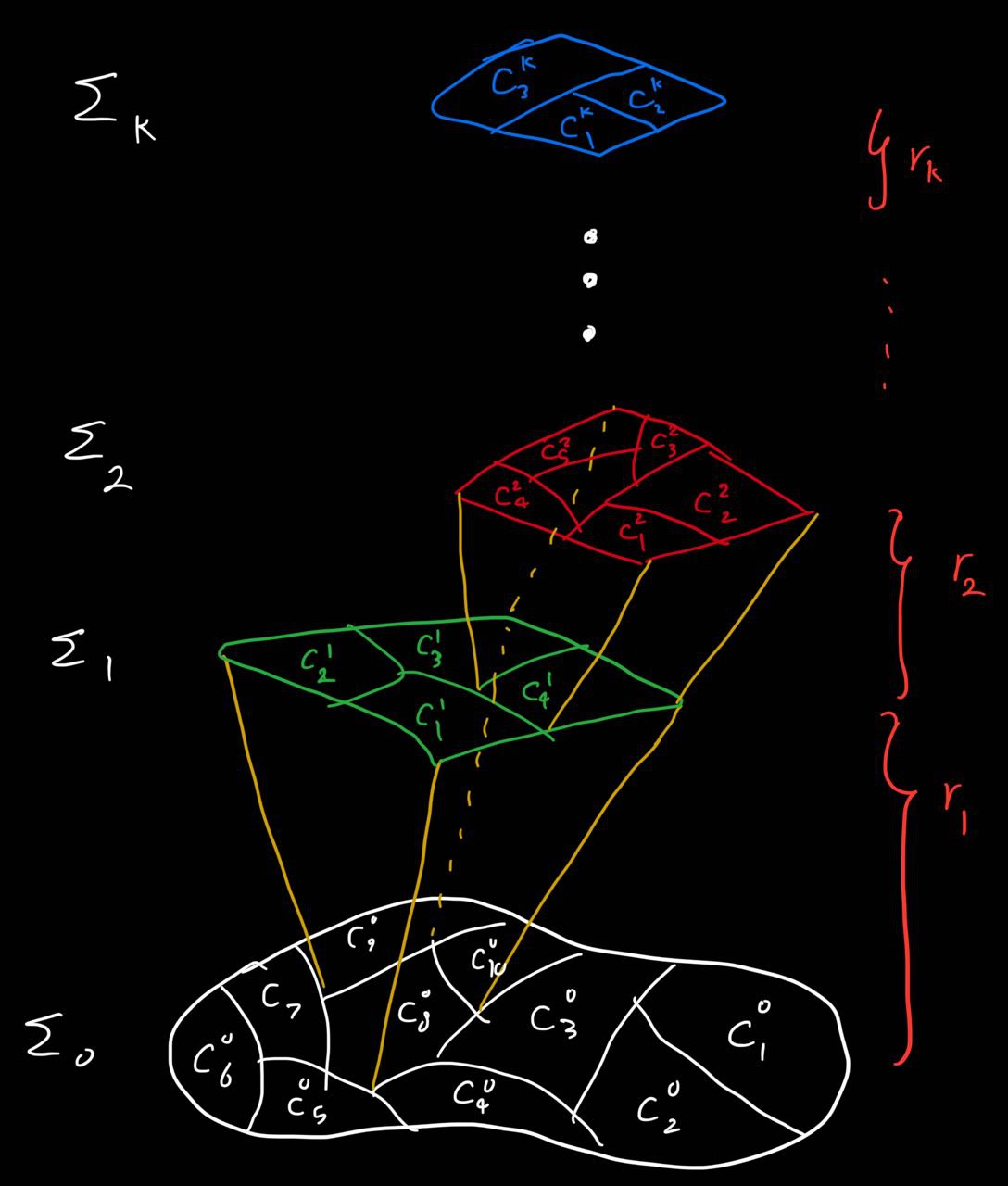

If we assume that the information is encoded in a probability space $(X, \Sigma, \mu)$, in order to organize this space in the most efficient way, we create a filtration as an increasing family of $\sigma$-algebras:

$$\Sigma_0 \subset \Sigma_1 \subset \cdots \subset \Sigma_{\infty}=\Sigma$$Each $\Sigma_k$ induces a finite (or countable) partition $\mathcal{P}_k=\{C_1^{(k)}, \ldots, C_{N_k}^{(k)}\}$ where each partition is mutually disjoint:

$$X=\bigsqcup_{i=1}^{N_k} C_i^{(k)}$$because $\Sigma_k \subset \Sigma_{k+1}$, every item at level $k+1$ sits inside a unique item at level $k$. You can see such a structure in the figure below:

For example a knife is inside the partition kitchen appliances and that itself in the partition house appliances etc. Formally, for every $C_j^{(k+1)}$ there is a unique parent $C_i^{(k)}$ such that $C_j^{(k+1)} \subseteq C_i^{(k)}$.

The filtration in this context is a tree. If there is fixed branching of $b$ at each level ($b$-ary tree), number of leaves at level $k$ is $N_k=b^k$. In other words, identifying an object (leaf) requires exactly $k=\lceil\log_b N_k\rceil$ $b$-way questions (in 2-way it is a yes/no question).

As it turns out this is the most efficient way of organizing information and that's also why the brain chooses such a hierarchical information storage that is based on the ratios of each level with the next.

What is "encoded"? Ratios between successive partitions

For any child $C_j^{(k+1)} \subset C_i^{(k)}$ define the ratio:

$$\rho_{k+1, j}=\frac{\mu(C_j^{(k+1)})}{\mu(C_i^{(k)})} \in(0,1], \quad \sum_{j: C_j^{(k+1)} \subset C_i^{(k)}} \rho_{k+1, j}=1$$An item $x \in X$ is located by a sequence of indices (the bit string) $(\rho_1, \rho_2, \cdots)$. The full probability of the deepest cell can be represented as:

$$\mu(C^{(k)}(x))=\prod_{m=1}^k \rho_m$$Thus the "payload" is multiplicative and logarithms convert it to an additive code:

$$\log \mu(C^{(k)}(x))=\sum_{m=1}^k \log \rho_m$$This is why logarithms, and log-normal statistics, pervade natural sensory coding: ratios become sums.

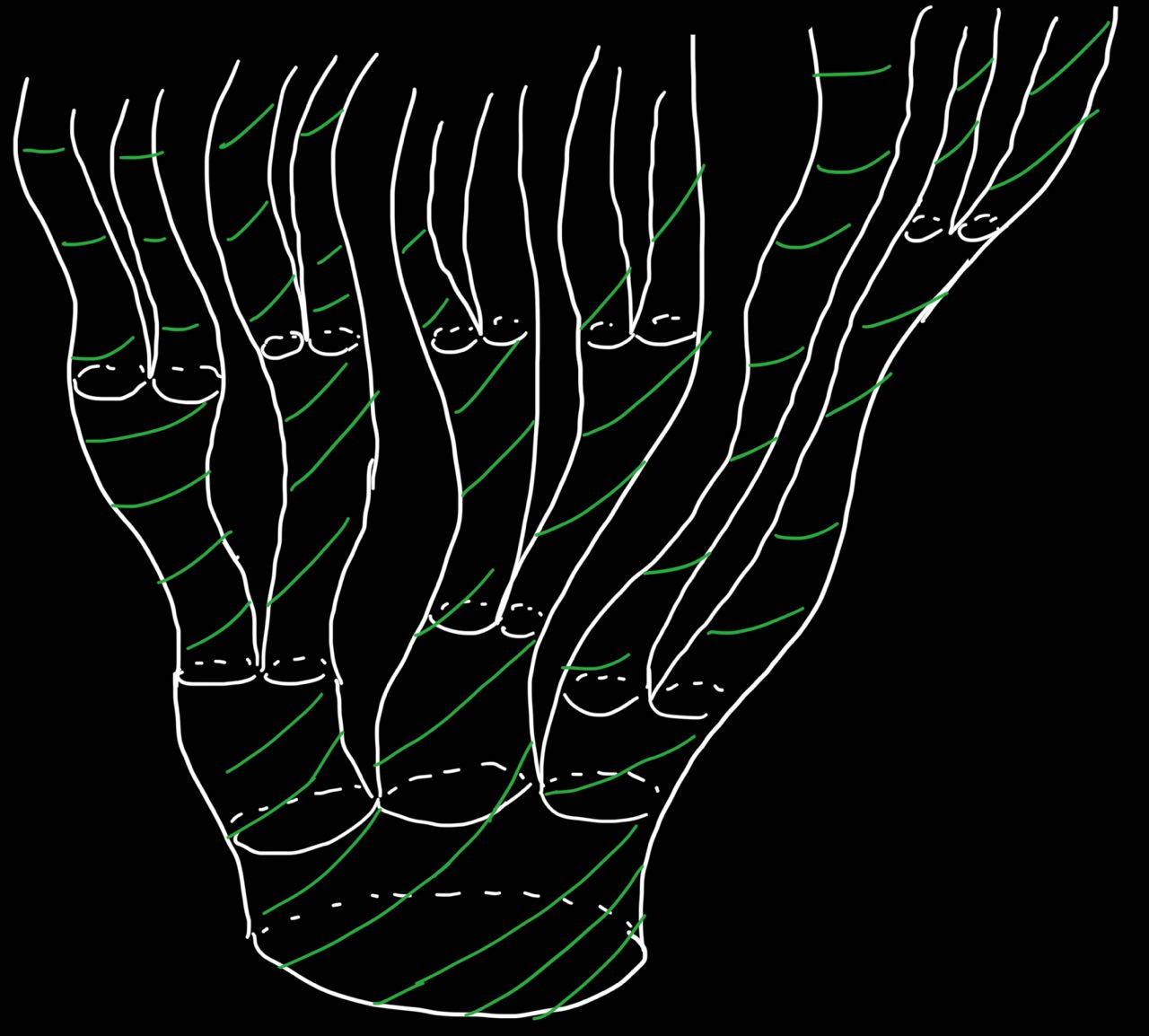

If the ratio at each level is the same we have a fixed ratio that represents the fractal dimension (information dimension). But in general, the ratios of each level (the branching factor) can be different. At level $k$ let the parent interval divide into $b$ sub-intervals:

$$\{\ell_{k+1, j}=r_{k+1, j} \ell_k, \quad p_{k+1, j} \mu(\text{parent})\}_{j=1}^b$$with geometry $\sum_j r_{k+1, j}=1$ and probability mass $\sum_j p_{k+1, j}=1$.

Now every path $(j_1, j_2, \cdots)$ acquires its own pair of products:

$$\ell_k(x)=\prod_{m=1}^k r_{m, j_m}, \quad \mu_k(x)=\prod_{m=1}^k p_{m, j_m}$$Taking logs and dividing gives a local Hölder exponent:

$$\alpha(x)=\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} \frac{\log \mu_k(x)}{\log \ell_k(x)}$$and different paths generically yield different $\alpha$. The fractal "blossoms" into a spectrum. $f(\alpha)$ is the Hausdorff dimension of the set of points that share that exponent.

Conclusion

We began with a simple but striking observation: that perception is not linear, but logarithmic, a quiet fact with sweeping implications. From there, we uncovered why this logarithmic structure is not just a coincidence of sensory systems but a fundamental organizing principle of the brain itself. It governs not only how we perceive, but also how we think, remember, and understand.

At the heart of this lies the brain's remarkable ability to interpret the world in terms of ratios, a faculty deeply tied to what we call code length. In information theory, code length is the logarithm of the number of possibilities, an efficient, compressed representation of complexity. The brain, and indeed the entire body, appears to embrace this principle. Cognition becomes compression: a continuous distillation of the flood of sensory inputs into meaningful relations.

Whether comparing tones, weights, brightness, or abstract ideas, our body seeks structure through proportion. It encodes the world by folding vast ranges of experience into compact, relational formats. This is not merely a strategy; it is the architecture of thought itself.

And so, behind every sensation, every decision, and every insight lies a deeper logic, a logarithmic mind that sees the world not as it is, but as it relates. In ratios, we find order. In compression, we find clarity. In the simple act of perceiving, we uncover the mathematics of meaning.

To understand is, ultimately, to measure the world by its ratios.

References

[1] Kusakabe, Y., Shindo, Y., Kawai, T., Maeda-Yamamoto, M., & Wada, Y. (2021). Relationships between the response of the sweet taste receptor, salivation toward sweeteners, and sweetness intensity. Food Science & Nutrition, 9(2), 719-727.

[2] Young, E. J., & Ahmadian, Y. (2023). Efficient coding explains neural response homeostasis and stimulus-specific adaptation. bioRxiv, 2023-10.

[3] Buzsáki, G., & Mizuseki, K. (2014). The log-dynamic brain: how skewed distributions affect network operations. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(4), 264-278.

[4] Petersen, P. C., & Berg, R. W. (2016). Lognormal firing rate distribution reveals prominent fluctuation–driven regime in spinal motor networks. eLife, 5, e18805.